Seri | Anything whatever

Of all time, really?

-Let’s put it differently, to avoid sounding pathetic and excessive, even when speaking the truth-precisely for want of tact: not of all time, perhaps, but ever since Aristotle suddenly hit on the manifold aporia of touch (aporia, he said then, and ap ores eie); ever since he, Aristotle, foresaw all the obscurities of the tangible: touch isn’t clear, ouk estin endēlon, he says furthermore; it’s adēlon, inapparent, obscure, secret, nocturnal. Let’s not put this off but say it: it is often the case in Aristotle that the diaporetic exposition, or within the exposition the moment that is properly diaporetic, is not necessarily a moment that can be passed or surpassed. By definition, one is never through with aporias worthy of their name. They wouldn’t be what they are -aporias- if one saw or touched their end, even if there were any hope of being done with them. It is thus necessary to treat them differently, and decide otherwise, where they couldn’t care less about our decision, and to let go, leaving ourselves in their hands in such a fashion, rather than any other, without any hope of stepping across them, or coming out on top, on the bottom, or by sidestepping-and even less by stepping back, or running to safety before them.

In Aristotle’s Peri psuchēs (On the Soul), what touches on touch always comes down to the unit or unity of one sense and its appearing as such. Yes, it comes to, first, the unit of sense of the sense termed touch; second, the unity of sense of the tangible; third, the unity of sense, between the two, of what refers touch to the tangible; fourth, the credit that we philosophers may here bring to common opinion, to doxa, with regard to this sensible unity of a sense. Let’s start over as clearly as possible, then, and quote the texts that lead onto the pathless path of these fo ur obscure aporias:

1. “It is a problem [aporia],” Aristotle says, “whether touch is a single sense or a group of senses. It is also a problem, what is the organ of touch; is it or is it not the flesh (including what in certain animals is analogous [substituted for “homologous”-Trans.] with flesh)? On the second view, flesh is ‘the medium’ [to metaxu] of touch, the real organ being situated farther inward” (Peri psuches 2.II.422b).

2. “Nevertheless we are unable clearly to detect [ouk estin endēlon] in the case of touch [te haphe] what the single subject [hupokeimenon] is which underlies the contrasted qualities and corresponds to sound in the case of hearing” (ibid.).

3. “[Since] that through which the different movements [causing the sensations fo r the senses other than touch-J. D.] are transmitted is not naturally attached to our bodies, the difference of the various sense-organs is too plain to miss. But in the case of touch [epi de tēs haphēs] the obscurity [adēlon] remains …. no living body could be constructed of air or water; it must be something solid …. That they are manifold is clear when we consider touching with the tongue [epi tes glottēs haphē]” (ibid., 423a).

4. “The following problem might be raised [aporeseie d’ an tis… ] …. does the perception of all objects of sense take place in the same way, or does it not, e.g., taste and touch requiring contact (as they are commonly thought to do [kathaper nun dokei]), while all other senses perceive over a distance? … we fancy [dokoumen] we can touch objects, nothing coming in between us and them” (ibid., 423a-b).

Aristotle is going to exert himself in questioning this doxa and, to a certain extent, in calling it into question. But only to a certain extent, there where what follows could take on the form of a “clear” thesis. Now, this is not always the case; at times the clarity of a proposition conceals another enigma. For example, though it is obvious or “clear” [dēlon] that, first, the “organ” of touch is “inward” or internal; second, flesh is but the “medium” of touch; third, “touch has for its object both what is tangible and what is intangible [tou haptou kai anaptou]” (ibid., 424a), one keeps asking oneself what “internal” signifies, as well as “medium” or “intermediary,” and above all what an “intangible” accessible to touch is-a still touchable un-touchable.

How to touch upon the untouchable? Distributed among an indefinite number of forms and figures, this question is precisely the obsession haunting a thinking of touch-or thinking as the haunting of touch. We can only touch on a surface, which is to say the skin or thin peel of a limit (and the expressions “to touch at the limit,” “to touch the limit” irresistibly come back as leitmotivs in many of Nancy’s texts that we shall have to interpret). But by definition, limit, limit itself, seems deprived of a body. Limit is not to be touched and does not touch itself; it does not let itself be touched, and steals away at a touch, which either never attains it or trespasses on it forever.

Let’s recall a few definitions, at least, without reconstituting the whole apparatus of distinctions holding sway in Aristotle’s Peri psuches.

Let’s first recall that sense, the faculty of sensation-the tactile faculty, for example-is only potential and not actual (ibid., 417a), with the ineluctable consequence that of itself, it does not sense itself; it does not auto-affect itself without the motion of an exterior object. This is a far reaching thesis, and we shall keep taking its measure with regard to touching and “self-touching.”

Let’s also recall that feeling or sensing in general, even before its tactile specification, already lends itself to being taken in two senses, potentially and actually, and always to different degrees (ibid., 417a).

Let’s mostly recall that touch was already an exception in the definition of sensible objects [especes du sensible] (each being “in itself” or “accidentally”; “proper” or “common”). Whereas each sense has its proper sensible object [idion] (color for vision, sound for the sense of hearing, flavor for the sense of taste), “Touch, indeed, discriminates more than one set of different qualities”: its object comprises several different qualities (ibid., 418a). Let’s be content with this initial set of signposts by way of an epigraph. Down to this day, these aporetic elements have not stopped spelling trouble, if one can put it like that, in the history of this endless aporia; this will be borne out at every step we take.

For, with this history of touch, we grope along no longer knowing how to set out or what to set forth, and above all no longer able to see through any of it clearly. An epigraph out of breath from the word go, then, to what I renounced trying to write, for a thousand reasons that will soon become apparent. For, to admit the inadmissible, I shall have to content myself with storytelling, admitting to failure and renunciation.

Hypothesis: it’s going to be a lengthy tale with mythological overtones -“One day, once upon a time … ” Pruning, omitting, retelling, lengthening, with little stories, with a succession of touches touched up again, off on one tangent and then another, that’s how I’m going to sketch the recollections of a short treatise dedicated to Jean-Luc Nancy that I have long been dreaming of writing peri Peri psuches, which is to say, around, on the periphery, and on the subject of Peri psuches- De anima-a murky, baroque essay, overloaded with telltale stories (wanting to spell trouble), an unimaginable scene that to a friend would resemble what has always been my relation to incredible words like “soul,” “mind,” “spirit,” “body, ” “sense,” “world,” and other similar things.

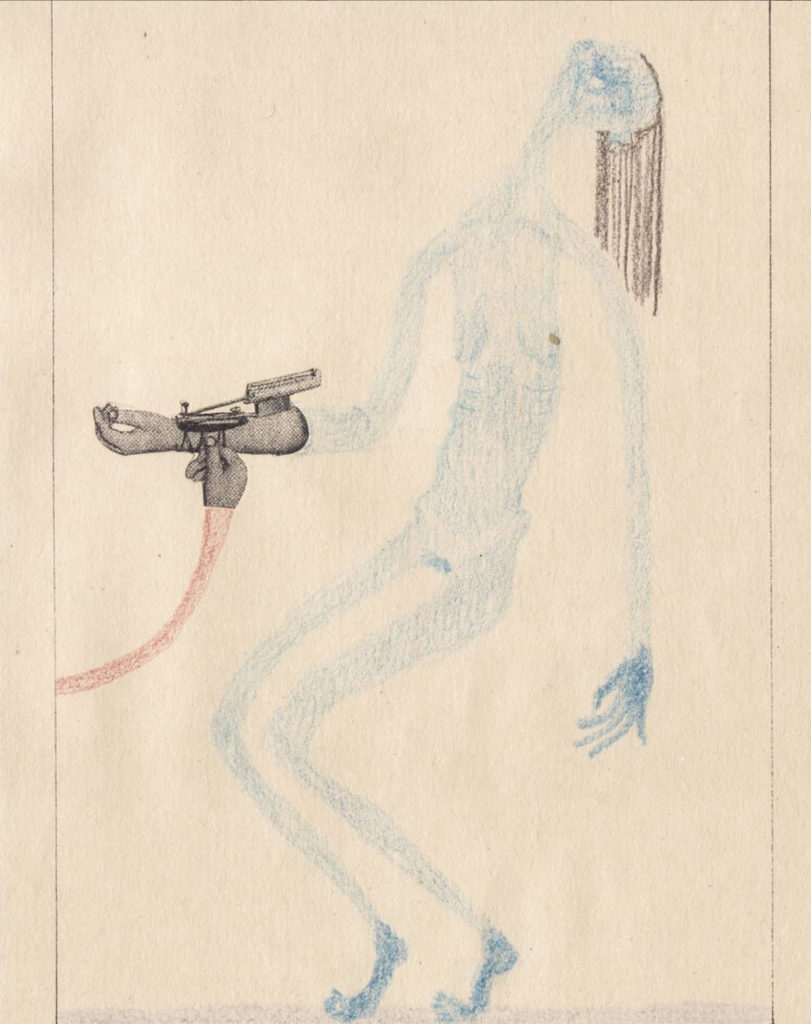

How can one have spent one’s life with words as defining, indispensable, heavy and light, yet inexact, as those? With words of which one has to admit that one has never understood anything? And to admit this while discharging oneself of any true guilt in the matter? Is it my fault if these words have never made any sense, I mean to say any exact sense-assured or reassuring for me-and have never had any reliable value, no more than the drawings deep in a prehistoric cave of which it would be insane to claim one knows what they mean without knowing who signed them, at some point, to whom they were dedicated, and so forth?

The difference is that I have never been able or dared to touch on these drawings, even be it just to speak of them a little; whereas for the big bad words I have just named (spirit, mind, soul, body, sense, sense as meaning, the senses, the senses of the word “sense,” the world, etc.), I dream that one day some statistics will reveal to me how often I made use of them publicly and failed to confess that I was not only unsure of their exact meaning (and “being”! I was forgetting the name of being! Yet along with touch, it is everywhere a question of “being,” of course, of beings, of the present, of its presence and its presentation, its self-presentation) , but was fairly sure that this was the case with everybody- and increasingly with those who read me or listen to me.

Now, we never give in to just “anything whatever”: rigor is de rigueur; and, to speak like Nancy, so is exactitude. “Exactitude” (we’ll come to it) is his word and his thing. He has reinvented, reawoken, and resuscitated them. That in a way is perhaps my thesis. It is thus necessary to explain – and that may be this book’s sole ambition – how Nancy understands the word “exact” and what he intends by it. I believe this to be rather new -like a resurrection. “Exact” is the probity of his signature.